NO VACCINE FOR THIS EPIDEMIC –

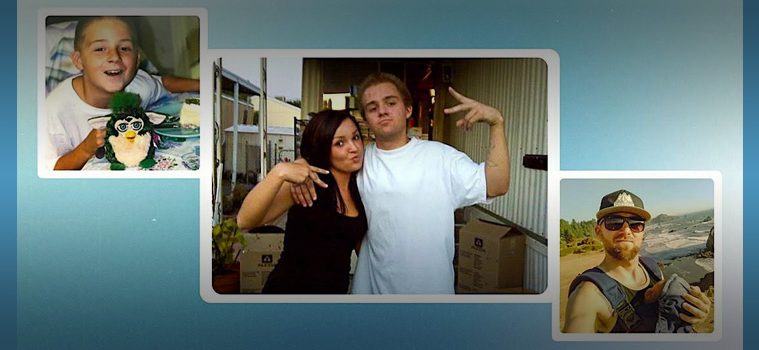

July 20, 2021 – If you had told me at any point in the last ten years while my brother, Jeremy, was battling his opioid addiction, that it would end in a St. Louis hospital listening to the beeping of machines, learning terms like anoxic brain injury and diabetes insipidus while a transplant team discussed organ donation, I would have insisted you were mistaken. I would have told you there was no way he would be brain dead by 30 years old. This was the reality, though.

On November 11, 2020, I got a call from my mom telling me that a woman found my brother unconscious and without a pulse in his truck on the side of a highway in St. Louis. The stranger had called 911, and when paramedics arrived on the scene, they spent eight minutes resuscitating him before transporting him to the hospital. Before I knew what I was doing, calls were made, credit card numbers were entered, bags were packed, and I was in a rental car racing through five states to get to him.

The world was still at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic when I arrived at St. Louis University Hospital, so I had to get my temperature checked when I entered the building and fill out contact tracing forms before I could actually see my brother. When I finally reached his room, I hesitated outside the door, intently focused on the 30 year old male label attached to it. There was no name or other identifying characteristics — it could have been anyone on the other side of that door. It was the first time I had seen my brother in four years, and those days in the hospital that followed would be the last moments I’d get with him. His nurse was finishing up in the room as I stood idly by, asking what they knew, which at that point wasn’t much. All they said was that if Jeremy’s condition didn’t change rapidly (for better or worse), someone would have to make the decision to turn off his ventilator or move him to a long-term nursing facility, where the chances of him being in a vegetative state forever were high.

When the nurse finally finished in his room and I was able to pull up a chair to sit with him, just the two of us, I reached for his hand, fixed my gaze on the exposed patch of skin on his arm covered with his first tattoo — a compilation of punk-rock-style stars he got before he turned 18 — and tried to think of what to say to him. I was surprised how strong he looked, even in his traumatic state. His dirty blond hair matted to the sides of his head, and he had a full, well-groomed beard. His broad shoulders filled out the delicate yellow hospital gown.