THE FUTURE IS RIGHT NOW –

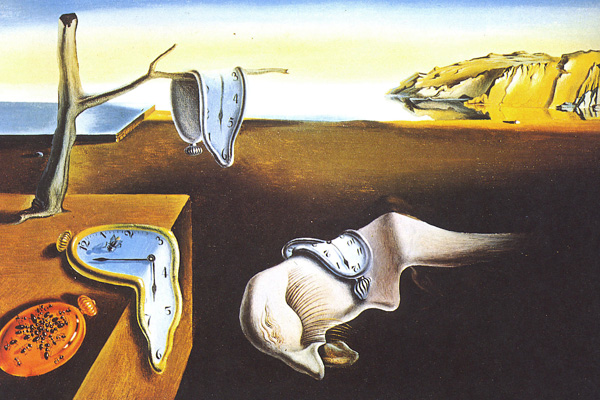

July 9, 2021 – It’s a strange, barely fathomable fact that our lives are lived through this small, moving window. Practitioners of mindfulness meditation often strive to rest their consciousness within it. The rest of us might encounter something similar during certain present-tense moments—perhaps while rock climbing, improvising music, making love. Thoughts of the future are often associated with anxiety and dread, and thoughts of the past can be colored by regret, embarrassment, and shame.

Still, mental time travel is essential. In one of Aesop’s fables, ants chastise a grasshopper for not collecting food for the winter; the grasshopper, who lives in the moment, admits, “I was so busy singing that I hadn’t the time.”

It’s important to find a proper balance between being in the moment and stepping out of it. On a group level, too, we struggle to strike a balance. It’s a common complaint that, as societies, we are too fixated on the present and the immediate future. In 2019, in a speech to the United Nations about climate change, the young activist Greta Thunberg inveighed against the inaction of policymakers: “Young people are starting to understand your betrayal,” she said. “The eyes of all future generations are upon you.” But, if their inaction is a betrayal, it’s most likely not a malicious one; it’s just that our current pleasures and predicaments are much more salient in our minds than the fates of our descendants. And there are also those who worry that we are too future-biased. ?

Meghan Sullivan, a philosopher at the University of Notre Dame, contemplates these questions in her book “Time Biases: A Theory of Rational Planning and Personal Persistence.” Sullivan is mainly concerned with how we relate to time as individuals, and she thinks that many of us do it poorly, because we are “time-biased”—we have unwarranted preferences about when events should happen. Maybe you have a “near bias”: you eat the popcorn as the movie is about to start, even though you would probably enjoy it more if you waited. Maybe you have a “future bias”: you are upset about an unpleasant task that you have to do tomorrow, even though you’re hardly bothered by the memory of performing an equally unpleasant task yesterday. Or maybe you have a “structural bias,” preferring your experiences to have a certain temporal shape: you plan your vacation such that the best part comes at the end.

For Sullivan, all of these time biases are mistakes. She advocates for temporal neutrality—a habit of mind that gives the past, the present, and the future equal weight. She arrives at her arguments for temporal neutrality by outlining several principles of rational decision-making. According to the principle of success, Sullivan writes, a rational person prefers that “her life going forward go as well as possible”; according to the principle of non-arbitrariness, a rational person’s preferences “are insensitive to arbitrary differences.”

Perhaps our biggest time error is near bias—caring too much about what’s about to happen, and too little about the future. There are occasions when this kind of near bias can be rational: if someone offers you the choice between a gift of a thousand dollars today and a year from now, you’d be justified in taking the money now, for any number of reasons. (You can put it in the bank and get interest; there’s a chance you could die in the next year; the gift giver could change her mind.) Still, it’s more often the case that, as economists say, we too steeply “discount” the value of what’s to come.

If near bias is irrational, Sullivan argues, so is future bias. Imagine, she writes, that you have trained for a triathlon for many months. Now it’s race day. The weather is fine, you’re healthy, but you just don’t feel like participating. Suppose you’re fairly certain that, if you don’t participate, you won’t regret your choice in the future. Should you race, even though you don’t feel like it?