OPINION by Maia Szalavitz –

Sept. 12, 2021 – But opioids are not cigarettes. And as the opioid settlements finally near completion, it is crucial not to misapply lessons learned from tobacco. Fundamentally, this means accepting that—unlike cigarettes—opioids have genuine uses in both pain and addiction medicine.

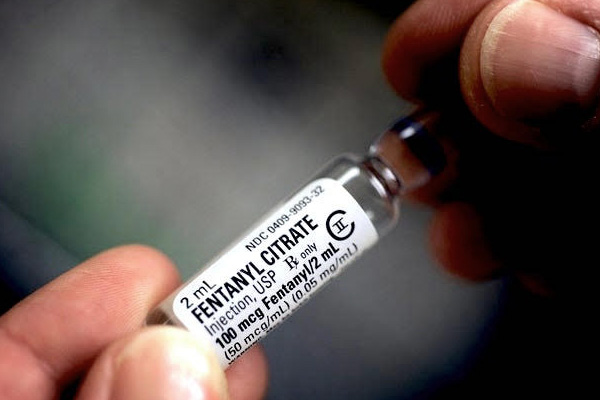

So far, however, we are doing the opposite. Rather than recognizing that some people with intractable pain benefit from opioids, we continue to reduce access— typically without offering affordable and effective alternatives. ather than acknowledging that closing “pill mills” and identifying “doctor shoppers” more often drives people to dangerous street drugs than to recovery, we frequently abandon patients in withdrawal. And instead of admitting that the best treatment for opioid addiction—the only one proved to cut the death rate by 50 percent or more—is medical opioids (typically buprenorphine or methadone, but some countries use heroin), we primarily offer abstinence-based treatment.

Understanding where the analogy between opioids and cigarettes holds—and where it goes astray—can guide better policy.

First, unlike for cigarettes, interrupting the opioid supply can kill rather than cure. One recent study of more than 100,000 patients published in JAMA examined dose reductions among people who had taken opioids for at least a year. Researchers expected these cuts to lower overdose risk.