Real Life Hollywood Horror –

September 16, 2020 – One death is a tragedy; two deaths are a pattern. As the strange events on North Laurel Avenue captured the attention of the national media, a shocking new detail came to light. It appeared that Buck was not a nobody. He was a Democratic Party “megadonor and political activist” (ABC News); a “prominent political activist” (NBC). He was “high-profile” (The New York Post); he was “high-powered” (Fox). Frustrated by the lack of response from law enforcement, the family of Gemmel Moore filed a wrongful-death lawsuit against Buck, the county and the district attorney. Their lawyers tallied several hundred thousand dollars in political contributions that Buck had made to Democratic candidates at all levels of office, from city to federal. They said that Buck was being shielded thanks to his political donations and status. They said that the county does not investigate crimes against Black gay men.

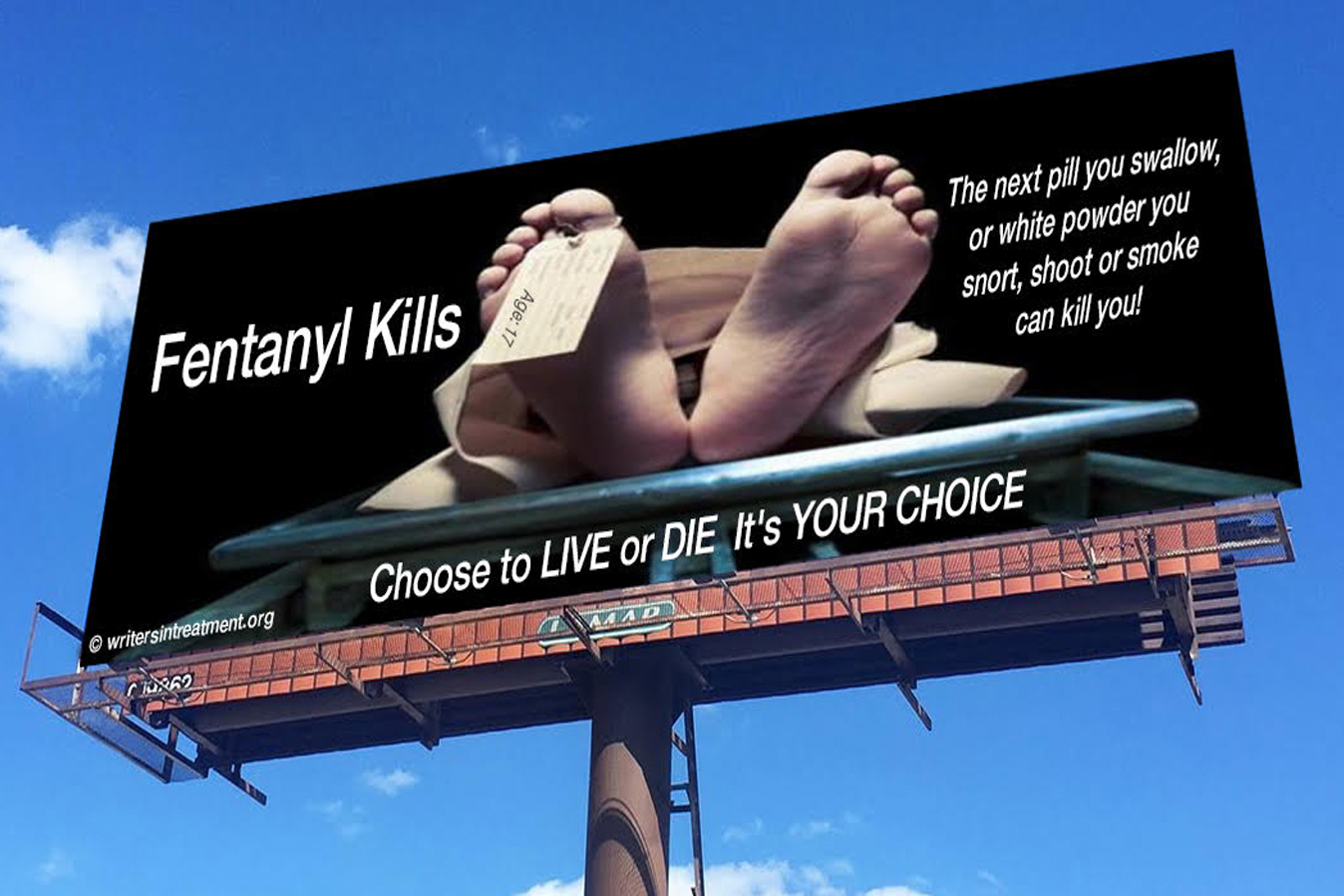

In the past decade, deaths in Los Angeles County related to meth overdose had increased 707 percent, from 50 in 2007 to 320 the year Moore died. Meth gave you a dopamine rush that was quick and enveloping. The supply was always plentiful. The Sinaloa cartel and its competitors moved the product from Mexico into Southern California, where distributors split up parcels and sent them into the city. The street price in Los Angeles stayed low, under $20 a dose, so meth was accessible to the very poor and homeless. The comedown made you twitchy and miserable; you could get addicted after your first time using. To the average medical examiner or L.A. County sheriff’s deputy in July 2017, the death of Gemmel Moore at the home of an older white john would have seemed like a sad, unremarkable story with familiar components: a sex worker, methamphetamine, bad luck.

The person with the power to bring a criminal case against Buck was Jackie Lacey, the first Black district attorney of Los Angeles County, and a Democrat. The day before the first anniversary of Moore’s death, Lacey announced that her team had completed an investigation and would not file charges. Demonstrators gathered outside 1234 North Laurel. Nothing changed, and they returned a year later. The signs said: “JACKIE LACEY: PROSECUTE ED BUCK.” “This is a national emergency for people who look like us,” said an activist named Jerome Kitchen, who is Black. Weeks passed, and no arrest was made.

On Sept. 11, 2019, at 5:20 in the morning, a man walked into the cashier’s booth at the Shell station on Santa Monica and North Laurel, three blocks from Buck’s apartment. The man was Black and wore jeans and a button-up shirt. His hand kept rising to touch his chest. “I think I’m having a heart attack,” he said.