HURTING CHILDREN AS POLICY –

July 2021 – Meehan started developing Enthusiastic Sobriety, which was both a theory and a practice. In order to entice teens, he believed, clean living needed to be just as fun—and just as reckless—as the alternative. If teens wanted to grow their hair long, smoke cigarettes, stay out all night, or even drop out of school, parents should let them—whatever kept them off drugs and alcohol was a good thing. Thus liberated, kids could enter the alternate social world of PDAP, which had its own dances, campouts, and house parties, all of them substance-free.

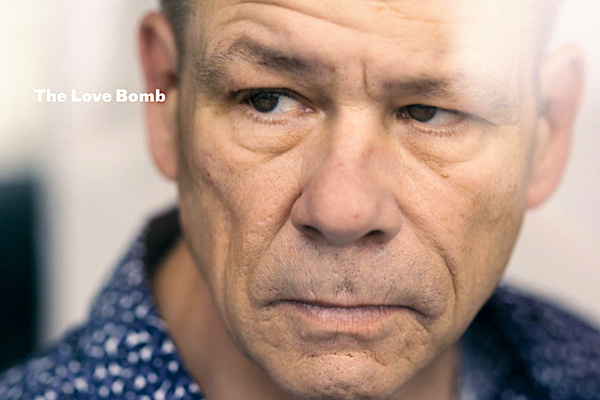

Spirituality was part of PDAP’s deal; much like AA, the program was rooted in the possibility of redemption. If that didn’t seem cool to teenagers, Meehan would be the first to tell them they were wrong. He believed that peer pressure was what drove young people to experiment with drugs and alcohol, and he aimed to use the same tactic to keep them sober. As soon as they walked in the door of a meeting, PDAP newcomers were smothered in hugs and people saying “I love you.” The tactic, called “love bombing,” is now widely recognized as a method for luring people into cults. One PDAP participant recalled thinking, “These guys are like the Hare Krishna or something. They’re going to try to make me sell flowers at the airport next week.”

In the program’s early days, Meehan met and married Joy DeFord, a diminutive, dark-haired divorcée who ran Palmer Memorial’s Alateen program, for teenagers who had alcoholics in their families. Joy came across as a polished Southern belle, a calm counterpoint to her manic husband, though she had quirks of her own, including an interest in hypnotism and homeopathy. The Meehans had a daughter and informally adopted a PDAP participant named Susan Lowry. Joy began running PDAP’s parent group, which held meetings each week. Hers was an essential role—PDAP’s smooth functioning depended on parents buying into the developing ES methodology.