NY Times Feature –

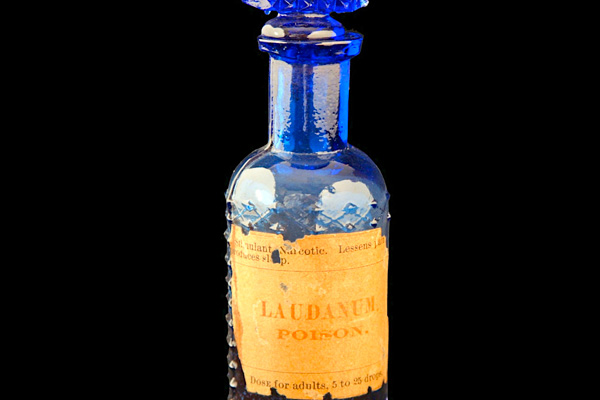

May 18, 2018 – A bottle of laudanum, a highly addictive liquid preparation of opium widely used as a painkiller and sleep aid in the late 19th century. After the death of her father, a prominent hotel owner in Seattle, Ella Henderson started taking morphine to ease her grief. She was 33 years old, educated and intelligent, and she frequented the upper reaches of Seattle society. But her “thirst for morphine” soon “dragged her down to the verge of debauchery,” according to a newspaper article in 1877 titled “A Beautiful Opium Eater.” After years of addiction, she died of an overdose. In researching opium addiction in late-19th-century America, I’ve come across countless stories like Henderson’s. What is striking is how, aside from some Victorian-era moralizing, they feel so familiar to a 21st-century reader: Henderson developed an addiction at a vulnerable point in her life, found doctors who enabled it and then self-destructed. She was just one of thousands of Americans who lost their lives to addiction between the 1870s and the 1920s. The late-19th-century opiate epidemic was nearly identical to the one now spreading across the United States. Back then, doctors began to prescribe a profitable and effective drug — morphine, taken via hypodermic needle — too liberally. After a decade of overprescribing it for minor ailments and even for issues related to mental illness, a colony of American junkies began to emerge.