ISN’T REAL LIFE IS SCARY ENOUGH? –

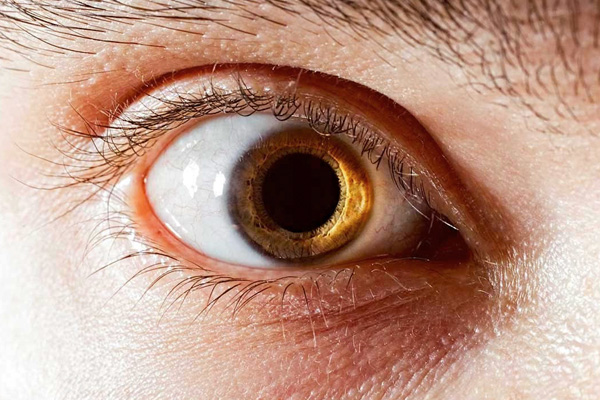

Feb. 19, 2022 – These psychotic episodes usually subside after a few days, but may persist for years in up to 15% of users.

While the link between amphetamine misuse and psychosis has been known for many decades, it’s not clear exactly what the magnitude is of this risk or how effective rehab is at successfully weaning users off the drug.

To try and find out, the researchers drew on information supplied to the Taiwan Illicit Drug Issue Database (TIDID) and the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) between 2007 and 2016.

The TDID contains anonymised data on date of birth, sex, arrest records and deferred prosecution for rehabilitation treatment for illicit drug users, while the NHIRD contains anonymised data on mental and physical health issues for the population of Taiwan.

The researchers identified 74,601 illicit amphetamine users and 298,404 people matched for age and sex as a comparison group from these records. Their average age was 33 and most (84%) were men.

Compared with those who weren’t using, illicit amphetamine users had poorer health: depression (2% vs 0.4%); anxiety (0.9% vs 0.3%); ischaemic heart disease (1.3% vs 0.8%); cardiovascular disease (0.8% vs 0.45%); and stroke (1.3% vs 0.7%).

By the end of the 10 year monitoring period, amphetamine users were more than 5 times as likely to experience psychosis than those who weren’t using after accounting for age, sex, and coexisting health issues.