WHEN 911 IS THE LAST RESORT –

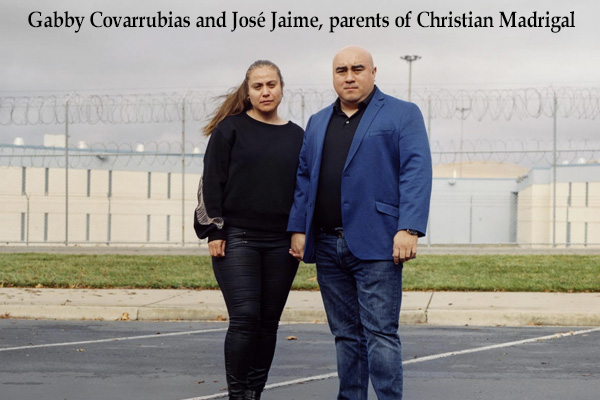

Jan. 30, 2021 – The moment their family members called 911, both Carlos and Christian became unwitting players in a system that is massive, complicated, and, according to many experts, manifestly broken. Both families would come to regret the decision to call the police for help, and Christian would not survive. “We were blind to the fact that something could happen to our son in that jail,” Jose told me. “Completely blind.”

Two weeks earlier, Christian had tried hallucinogenic mushrooms for the first time, and he hadn’t been normal since. “When you looked him in the eyes, he was not our boy,” Jose told me. “His eyes were different. His face was different. Everything was different.”

Jose said when the Fremont police arrived, they called for backup and ordered that Christian be brought outside. There, they arrested him for being under the influence of a controlled substance, although his parents maintain that he hadn’t used any drugs since he ingested the mushrooms. When they led him outside the house, Christian began crying out to his mother for help. She and Jose stood by in shock, not knowing what to do. Carlos and Christian weren’t just unlucky. They’re representative of a decades-long pattern of filling up jails with mentally ill people. When policy makers began closing state-run psychiatric hospitals in the 1950s, they promised to replace them with localized mental-health care—but in most places the funding and political will required to make this happen never materialized, leaving large swaths of the U.S. without any options for those seeking treatment. A conservative estimate says 900,000 people with mental illness end up in our jails every year. “These are people who are not necessarily intending to perform criminal acts,” Christine Montross, a psychiatrist and author of Waiting for an Echo: The Madness of American Incarceration, told me.