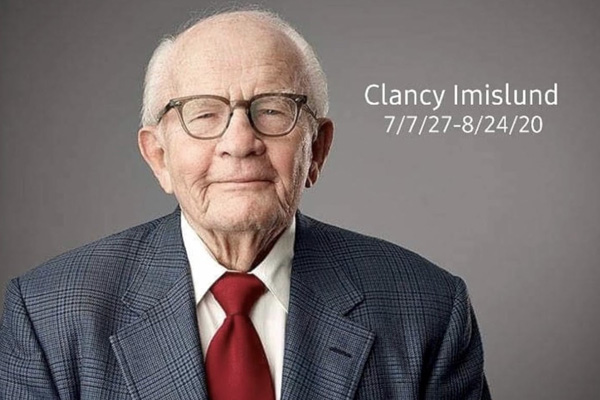

Obituary – A most famous anonymous man –

Sept. 3, 2020 – Along the way, he left a lucrative career with a Beverly Hills marketing firm to become managing director of the Midnight Mission in downtown Los Angeles’ skid row, returning as a transformative leader to an institution that had once kicked him out for bad behavior. Under his hand, the soup kitchen and housing facilities grew with programs to address the social needs of skid row, said its president and chief executive, G. Michael Arnold.

“He’s probably the first person to bring substance use treatment to people living on skid row,” Arnold said.

Evolving from executive to ambassador-at-large, Imislund held the title of managing director for the next 46 years until his death on Aug. 24 at 93.

He left a legacy in the quasi-secret world of AA unmatched by any but founders Smith and Bill Wilson, said Stephen Watson, a Midnight Mission board member and one of the roughly 170 people Imislund was sponsoring up to his death.

Imislund died of an undetermined cause while in isolation following a positive test for the coronavirus, his daughter Mary Imislund Dougherty said. He was undergoing rehabilitation for a broken hip and was at the end of the isolation period when the rehabilitation center informed her of his death, she said.

Growing up in a Norwegian Lutheran family in Eau Claire, Wis., Imislund discovered, as he would later say, that “I seem to need more fun than other Lutherans somehow.”

By the time he was 15, straight A’s and self-discipline were behind him.

“I have a flair for doing the wrong thing, to almost instantly do the worst thing I could have done,” he said.

The attack on Pearl Harbor offered an escape. He hitchhiked to San Francisco intending to make something of himself as a war hero. Stints in the merchant marine, then the Navy introduced him to whiskey and tobacco to the betterment of his self-image if not his character.

“I felt like men looked,” he said of his emotional reaction to alcohol.

After the war Imislund returned to Wisconsin, enrolled in college, married Charlotte, “this girl with flashing black eyes and black hair,” and settled into what he would later recognize to be the normal life of an alcoholic.Nights with family punctuated by nights in jail culminated in a vow of sobriety, made over the coffin of his first son, who died on a frigid winter night when Imislund was jailed and didn’t make it home to restart a finicky heater.

“John Imislund, this will never happen again.” It was a vow made to be broken.

The family moved a lot. The time in El Paso stands out as the pleasantest of her life, his daughter said.

Her father, a talented self-taught musician, partied at home with the city’s marijuana-smoking jazz musicians.

“My happiest memories are laying in my bed, smelling that smell, hearing that music,” she said.

In Texas, Imislund had great jobs, Mary said, among them even directing the Grand Opera at the University of Texas. But he always lost them, falling victim to what he would describe as the recurring “spring in my gut” that made him restless, eventually turning the world from “technicolor to black and white.”

A nearly successful suicide attempt led to a mental commitment and electric shock therapy.

Thorazine and tequila followed. The night he went out to buy food for his new daughter Susan and didn’t come back, Charlotte packed up the kids and resettled in a one-bedroom apartment.